Benthic Monitoring

Benthic monitoring for the Lower Cape Fear River Program, conducted by the UNCW Benthic Ecology Laboratory under the guidance of Dr. Martin Posey and Mr. Troy Alphin, began in spring 1996. This monitoring effort, which focuses on the upper oligohaline estuary down through the lower polyhaline estuary, targets the benthic infauna (sediment grabs). Other projects in the Benthic Ecology Laboratory compliment this sampling effort and include epibenthic trawls and juvenile Blue Crab ( Callinectes sapidus) research in the estuary.

The benthic monitoring component has four major long-term objectives:

- Characterize the benthic communities in the Lower Cape Fear River and compare them with other river-dominated estuaries to gain a first-order assessment of estuarine health

- Determine seasonal, annual and spatial patterns of variability

- Establish correlations between benthic abundances and physical measures

- Establish a baseline for detecting changes in the estuarine community through examination of changes in abundances of specific indicator taxa and eventual application of standard benthic indices.

Fisheries Research and Monitoring

In January 1997, a comprehensive survey of fish populations in the tidal freshwater portion of the Cape fear basin was initiated, led by Dr. Mary Moser (UNCW). In the summer of 2000, the program was taken over by Dr. Thomas Lankford and Michael Williams (UNCW). The objectives of this survey were to:

- Characterize fish community structure

- Document the incidence of fish disease

- Monitor non-native species populations

- Track the effects of hurricanes on the fish community.

This survey, a cooperative effort between the Cape Fear River Program (UNCW scientists, gillnets and electroshocking) and the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries (NCDMF, Wilmington Office, trawl), employs three gear types in order to examine a broad segment of the fish population.

Anadromous Species of the Cape Fear River System

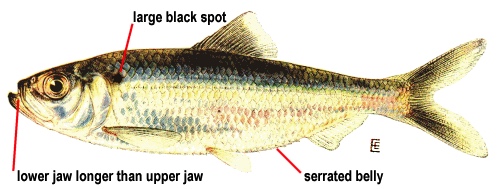

American Shad, Hickory Shad

Throughout the history of settlement on the Cape Fear River, the spring spawning run of the American shad ( Alosa sapidissima) and Hickory shad ( Alosa mediocris) has supported a very important commercial and recreational fishery. Commercial landings of these species have shown a gradual decline since the early 1970’s, indicating a decrease in their population size. To stem any further decline in their numbers, the North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries enacted a Fisheries Management Plan for the American shad. In 1998 an amendment to the Interstate Management Plan for American Shad included a phase out of the offshore shad fishery over a five-year period beginning in 1999. American shad migrate from Canada to Florida. The offshore fishery intercepts shad that are migrating south to spawn in the rivers and streams they originated from. If North Carolina shad are being captured in Massachusetts, resource managers here cannot regulate the shad fishery properly. With the offshore phase out, the inshore Cape Fear River shad fishery will become even more important. Catch-Per-Unit-Effort data have shown large fluctuations over the four seasons of sampling, but no distinct trends or statistically significant changes.

An American shad with abdomen cut away revealing the roe.

Hickory Shad

Striped Bass

Striped bass ( Morone saxitilis) are one of 7 anadromous species found in the Cape Fear River system. Due to dramatic drops in the population, a coast wide moratorium on striped bass fishing was imposed from 1985 to 1990. Although striped bass populations in other N. C. drainages have rebounded, the Cape Fear River striped bass population has not (Mallin et. al. 1998,1999,2000). Although declines in water quality and the introduction and possible predation and competition by nonnative catfishes are probably contributing to the problem, one specific culprit could be competition from hybrid striped bass. Gillnet surveys showed the average catch-per-unit effort of striped bass from 1990 to 1992 was cut in half when compared to the catch-per-unit average from 1996 to 1999. Unfortunately, the same survey showed a more than doubling of the catch-per-unit-effort of hybrid striped bass during the same time period (Patrick and Moser 2000). Tag and recapture data and the capture of spent hybrid females also indicate that the hybrid striped bass conduct a spawning run with the striped bass and may be competing for mates and spawning habitat. The true striped bass and the hybrids have a very high diet overlap. If food resources, spawning habitat, or spawning partners are limited, it is likely that the hybrids are depressing the true striped bass population in the Cape Fear. Despite a significant increase in the 1999 spring shocking and trawling catch-per-unit-effort, overall striped bass abundance remains low in the Cape Fear River system.

Hybrid-striped Bass

Hybrid striped bass are a hybrid of striped bass ( Morone saxatalis) and white bass ( Morone chrysops). They have been stocked as a put and take fishery in Lake Jordon nearly every year since 1983. The hybrids are introduced to the Cape Fear River by flooding events. Through competition, hybrids utilize the resources normally available to striped bass (Patrick and Moser 2001). Hybrids do not reproduce and so the resources they keep from striped bass are not converted into reproduction. As a result of competition with hybrids, striped bass may not be as healthy and in turn, not produce as many juveniles. Tag and recapture data from studies conducted in this drainage suggested that hybrids conduct a spawning run with true striped bass as has been documented in other systems (Patrick and Moser 2001, Bishop 1967). Due to competition with true striped bass for food resources and spawning habitat, hybrid striped bass are likely having a negative impact on the striped bass population in the Cape Fear River system. Catch-per-unit-effort data showed a statistically significant drop in the fall gill net samples (Figure 32). While commercial landings of striped bass in North Carolina have shown a gradual increase since 1990. Landings in the Cape Fear System remain low and this is the only river in North Carolina that stocks hybrid striped bass. Although the hybrid striped bass population appears to be decreasing, future surveys should examine whether this trend continues.

Dr. Thomas Lankford holding a striped bass.

A hybrid striped bass

Alewife, Blueback Herring

Atlantic Sturgeon, Shortnose Sturgeon

Historically, North Carolina supported a large sturgeon fishery. Due to overfishing, habitat degradation, and the Lock and Dam system construction, the Atlantic sturgeon ( Acipenser oxyrhynchus) is currently classified as a threatened species in North Carolina and their possession has been banned since 1991. The shortnose sturgeon ( Acipenser brevirostrum) also occurs in this drainage (Moser and Ross 1995) and has undergone such a dramatic population decline that it has been federally listed as a endangered species. Both species of sturgeon can live over 60 years. While the shortnose reaches it’s maximum size at around 100 cm (3.33 feet) the Atlantic sturgeon can attain sizes exceeding 300 cm (9.8 feet) and 270 kg (>600 pounds). Sturgeon are harvested for the meat, their swim bladders to make insinglass, the cartilagenous backbone to make emulsifiers and thickeners, their skin to make leather products, and most importantly, the roe, which can be made into high quality caviar (Williams and Moser 1999). With American sturgeon caviar currently selling for $192.00 a pound and smoked sturgeon selling for $14.00 a pound, sturgeon fishing can be very lucrative. Unfortunately, Atlantic sturgeon reproduce for the first time between 7 and 28 years, depending on their latitude. With the fishery being so lucrative and the fish having to go through a minimum of 7 years of fishing pressure before they can reproduce, overfishing can quickly become a problem. Recent catches of ripe sturgeon and the regular catches of juveniles in this survey indicate a reproducing population in this drainage. Catch-per-unit-effort from this survey shows a fluctuating but stable juvenile population in the Cape Fear River system.

Michael Williams greeting an Atlantic Sturgeon that he surgically implanted a sonic tag in 1 year and 29 days earlier.

A seven-foot female Atlantic Sturgeon that was captured in the Cape Fear River on March 24, 2000.

Nonnative Fishes of the Cape Fear River System

Blue Catfish

The blue catfish ( Ictalurus furcatus) was introduced to the Cape Fear River by the Wildlife Resources Commission in the attempt to create a trophy fishery (Moser and Roberts 1998). Although blue catfish were uncommon in the 1970’s, they are currently the most abundant species captured in our gillnet survey (Mallin et. al. 1998,1999,2000). The success of the blue catfish in the Cape Fear River system is likely due to it’s generalist feeding behavior. Gut content analyses have shown this species to feed on a wide range of prey including snakes, birds, fish, shrimp, worms, eels, grapes, other fish and surprisingly clams. Over 75% of the stomachs examined contained an Asian fresh water clam ( Corbicula fluminia) that was introduced by a bilge discharge in the Wilmington harbor in 1975 (Williams and Moser, in prep). Although thought to have aided in the demise of our native catfish population through competition, blue catfish are a popular sport fish and support a small commercial fishery in the Cape Fear River. Disease percentages ranged from 28% in the fall of 1999 to less than 1% in the spring of 2001 (Mallin et all 2000). Although there have been no significant changes in catch-per-unit-effort (Figure 26), this species will be monitored closely for information on the cause of the disease percentage fluctuations.

Flathead Catfish

In 1966 the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission introduced the flathead catfish ( Pylodictis olivaris) to the Cape Fear River in an attempt to create a trophy fishery (Moser and Roberts 1998). Within 15 years of their introduction, the flathead catfish was found to be the most abundant catfish by weight and considered to be the new dominant predator in the Cape Fear (Guier et. al. 1981). Guier’s study in the late 1970’s showed that fish (99.4% by weight ) were the principle prey of P. olivaris. Catfishes were the dominant fish found in the flathead’s diet (Guier et al. 1981, Ashley et al. 1989). This is a strong indication that the introduction of this species has led to the severe decline of our native catfish populations. Since 1997 only 2 native catfish have been captured while 1618 blue catfish, 193 channel catfish, and 198 flathead catfish have been captured. Thus less than 0.1% of our catfish captures are native species. Future studies should reexamine the diet of flatheads to determine which prey species are currently being exploited as a food source. Flathead catfish exhibited a statistically significant decrease in the fall 2000 but exhibited a statistically significant increase in spring 2001 gillnet catch-per-unit-effort (Figure 30). Reasons for these changes are yet unknown but will be addressed in future surveys.

Channel Catfish

Channel catfish were introduced into the Cape Fear in the early 1900’s (Smith 1907). A small but stable population was established that persisted through the 1970’s. In recent years, however, this species has shown “reductions in relative abundance since the introduction of the blue and flathead catfishe s.”(Moser and Roberts 1998). The decline is likely due to competition with blue catfish. This survey shows no statistically significant changes in catch-per-unit-effort (Figure 28) and a low incidence of disease since 1997.

Grass Carp

Grass carp ( Ctenopharyngodon idella) are another non-native species of concern. Grass carp have reached sizes of over 60 pounds in this state. They are herbivores and have been introduced to reservoirs and ponds throughout the Cape Fear River basin to control aquatic vegetation. When they are introduced to the Cape Fear by flooding events, however, they consume aquatic vegetation that functions in controlling erosion and as nursery habitat for juvenile fishes. The state of North Carolina recognized the potentially destructive habits of this species and requires that all grass carp be certified as triploid before they can be introduced to ponds and reservoirs. A recent study in the Chesapeake Bay found that although stocking of non-sterile grass carp has been illegal since 1979, 18% of the feral grass carp collected in Chesapeake bay tributaries were not triploid. The researchers speculated that the non-triploid carp originated from illegal stocking efforts or had been introduced them before the regulations were put into place (Schultz et. al. 2001). If a mistake has been made and 100% of the grass carp introduced were not sterile, then there could be a reproducing population of grass carp in the Cape Fear. If conditions are favorable, it takes only a few individuals to populate a river system. An example would be the flathead catfish. Eleven individuals were introduced in 1966 and they are now one of the dominant predators in the Cape Fear River system. A reproducing population of non-native grass carp could thus severely impact our fisheries resources (Raibley et al. 1995). There was no statistically significant difference in catch-per-unit-effort between years. Although more were captured in the fall of 1999 than all previous years combined, there is a trend toward decreasing catches of grass carp since that time. Although the documented trend is encouraging, monitoring of this species should remain a priority of this survey to examine changes in population levels and determine if they indicate reproduction in this river system.

Common Carp

Redear Sunfish

Redear sunfish ( Lepomis macrochiris) are another introduced species in the Cape Fear. In this survey they are the second most abundant sunfish captured after bluegill. They are an important pert of the forage base and support a popular recreational fishery. Although not statistically significant, there has been a trend toward increased catch-per-unit-effort in the spring electroshocking samples (Figure 36). Disease percentage average continues to average approximately 4 percent with no significant trends.